Getting Started with Parallel Programming

自我感觉很不错的一篇文章,介绍并行计算的。

Multi-core computers have shifted the burden of software performance from chip designers to software architects and developers. In order to gain the full benefits of this new hardware, we need to parallelize our code. The goal of this article is to introduce you to parallelism, its different types and to help you understand when to parallelize your code - and when not to. We will also examine some of the tool options developers have today for building parallel applications.

Introduction to parallelism

Traditionally, computer systems have consisted of a processor, a memory system, and various other subsystems. The processor would execute instructions sequentially, which meant that the vast majority of software was typically written for serial computation.

While we were able to improve the speed of our processors by increasing the frequency and transistor count, it was only when computer scientists realized that they had reached the processor frequency limitation that they started to explore new methods for improving processor performance. These included the use of the germanium instead of silicon, co-locating many low frequency and power consuming cores together, adding specialized cores, 3D transistors, and others.

Now we live in the era of multi-core processors. Exploiting large-scale parallel hardware will be essential for improving application performance and its capabilities in terms of executing speed and power consumption.

Parallelism from a software perspective

Parallelism is a form of computation in which many calculations are carried out simultaneously, operating on the principle that large problems can often be divided into smaller ones, which are then solved concurrently, or ‘in parallel’. Parallelism is all about decomposing a single task into smaller ones to enable concurrent execution.

Parallelism vs. Multithreading - You can have multithreading on a single-processor machine, but parallelism can only occur on a multi-processor machine. In other words, simply creating more threads will not change your application architecture into a parallel architecture. Today, mainstream developers are comfortable with multithreading and they usually use it for three kinds of scenarios:

- Background work for better UI response

- Asynchronous I/O operation

- Event-Based, asynchronous patterns

Parallelism vs. Concurrency - You can refer to multiple running threads as being concurrent but not parallel. Concurrency is often used in servers that operate multiple threads to process requests. However, parallelism is about decomposing a single task into smaller ones to enable execution on multiple processors in a collaborative manner to complete one task.

Parallelism vs. Distributed Systems - Distributed systems are a form of parallel computing; however, in distributed computing, a program is split up into parts that run simultaneously on multiple computers communicating and sharing data over a network. By their very nature, distributed systems must deal with heterogeneous environments, network links of varying latencies, and unpredictable failures in the network and the computers.

Types of parallelism*

There are two primary types of parallelism:

- Task Parallelism

- Data Parallelism (a.k.a. Loop-Level parallelism)

Task Parallelism

When your application can be thought of as a group of tasks that can execute simultaneously on multiple processors, you have Task Parallelism. Tasks are assigned to threads and may execute on the same or different data. The threads may execute the same or different code.

For example, Task Parallelism can be used when:

- You need to execute four computations, but you don’t care which one will finish first

- You want to load, process, and save many different image files, so you process individual files in parallel

Data parallelism

Data Parallelism applies the same instruction to each data element in a thread safe way. It is also known as loop-level parallelism and is similar to SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data). On the other hand, MIMD (Mutiple Instruction, Multiple Data) applies different instructions to different data. SIMD and vectorization are techniques employed by modern processors to achieve data parallelism.

Data parallelism can be used when:

- You have a large bitmap image and the processing of each pixel is independent

- You need to search through a large, unsorted collection of data

There are two types of data parallelism:

- Explicitly Data Parallel

- Implicitly Data Parallel

In Explicitly Data Parallel you just write a loop that executes in parallel, as I mentioned earlier. This can be done by adding OpenMP pragmas around the loop code, or using a parallel algorithm from Intel® Threading Building Blocks (TBB) (See the ‘Additional Resources’ section below).

In Implicitly Data Parallel you just call some method that manipulates the data and the infrastructure (i.e. a compiler, a framework, or the runtime) and is responsible for parallelizing the work. For instance, the .NET platform provides LINQ (Language Integrated Query) that allows you to use the extension methods, and lambda expressions to manipulate the data like dynamic languages.

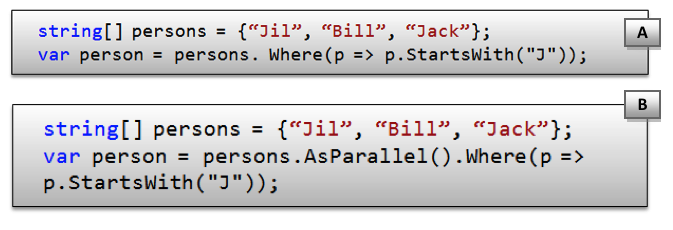

The following figure demonstrates implicit data manipulation and parallelism:

A: C# implicit data manipulation using LINQ

B: C# parallel implicit data manipulation using LINQ (Note the AsParallel method)

Libraries and compiler-based parallelism

There are two primary types of parallelism frameworks and infrastructure:

- Language extensions and compiler-based parallelism

- Library-based parallelism

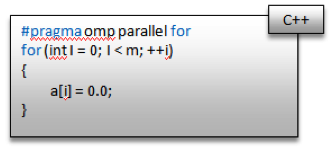

In language and compiler-based parallelism, the compiler understands some special keywords to parallelize part of the code; for example, in OpenMP you can write the following to parallelize a loop:

Language and compiler-based parallelism is easy to use because the majority of the work falls on the compiler.

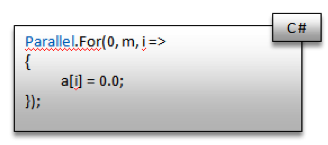

In library-based parallelism, the programmer should call the exposed parallel APIs. For example, if you want to parallelize a for loop in .NET 4 (C#, or VB) you should call a For method from the System.Thread.Parallel class:

This method accepts two integers (from, to) and delegates to the loop body.

Parallelism challenges

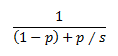

In order to take advantage of multi-core machines, programs must be parallelized. Multiple paths of execution have to work together to complete the tasks the program has to perform, and that needs to happen concurrently, wherever possible. Only then is it possible to speed up the program (i.e., reduce the total runtime). Amdahl’s law expresses this as:

Where P is the percentage of the program that can be parallelized, (1-P) is the percentage of serial execution, and S is the number of execution units. This is the theory. Making it a reality is another issue.

Parallelism is hard. If you decide to modify your application to a parallel architecture, you will need to address several issues, such as: Which part of your application should you parallelize and how? How significantly should you alter your application? What should you avoid parallelizing? Answering these questions requires not only technical expertise but also strategic thinking that evaluates the benefits and costs.

When to parallelize your code Parallelism won’t benefit the entire application, so you should ask yourself first: do I even need to move to a parallel architecture in the first place? You probably don’t need to parallelize:

- Really simple applications

- Unoptimized serial code

- Serial code that is running fast enough already

Which part of your application to parallelize is another critical question you need to ask. Parallelism by nature has overhead to start and manage the threads and the tasks, so you should choose the part of your application that really stands to benefit from a parallel architecture. From my experience, this comprises 20% of the application code, but this can be 60% or more if you application is a high-performance computing application, or a 3D game, etc. Here are some guidelines on how to identify the right part of your application to parallelize:

- Use a profiler. A profiler can help you identify the hot spots of your application, the spots that consume a lot of processing time. In the profiler report focus on the algorithms that take a significant amount of execution time and might benefit from parallel processing: sorting algorithms, code for filtering or processing chunks of data, etc.

- Don’t parallelize I/O reading, or writing code except if you know that your target machine has fast I/O components such as RAID HDD.

- Be sure that your parallel tasks contain enough computations to make the parallel execution worthwhile. For example, parallelism will not speed up sorting 100 elements (in fact, it might slow this down); however, if you sort 100,000 elements, parallelism could make a difference.

The technical challenges Dealing with shared data is perhaps one of the first challenges you will face when you start to write parallel code. In my opinion, I think this is really the main parallelism challenge.

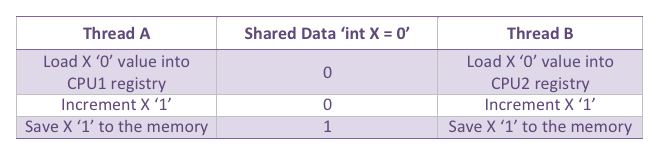

To understand the shared data challenge, imagine having two threads that update a shared variable in parallel:

The middle column shows the status of the shared data , and the other columns show the threads instructions. When the threads load the initial value of X to increment it, it will be the same ‘0’, which means that the finial value will be 1 instead of 2 (i.e. both threads don’t know that X has been fetched into another CPU registry to increment).

So we need some kind of atomic operations, or lock to control the shared data modification. However, use of locks add overhead and minimize the performance benefits. They can also lead you to deadlocks. Still, they may be necessary to ensure that the correct answers are computed. Managing locks and minimizing their impact is another major challenge to writing parallel applications.

Parallelism in the real world

Regardless of the challenges, parallelism is being used to solve some very real business problems in various application domains: server applications, high performance computing environments, and in the gaming industry. Today, parallelism continues to enter into the world of mainstream software development.

Servers have long been the main types of parallel and concurrent systems that have enjoyed commercial success. Their main workload consists of mostly independent requests that require little or no coordination and share little data. As such, it is relatively easy to build a parallel Web server application, since the programming model treats each request as an independent sequential computation. Building a Web site that scales well is an art; scale comes from replicating machines, which breaks the sequential abstraction, exposes parallelism, and requires coordinating and communicating across machine boundaries.

High-Performance Computing followed a different path to using parallel hardware and parallel software because there is no alternative with comparable performance. Commonly HPC relies on distributed systems that are designed to work in parallel to achieve satisfactory performance.

Today, popular programming models such as MPI and POSIX Threads are performance focused, error-prone abstractions that many developers find difficult to use. To address this shortcoming, OpenMP and TBB attempt to further abstract the details from the programmer to make parallel programming easier and less error-prone.

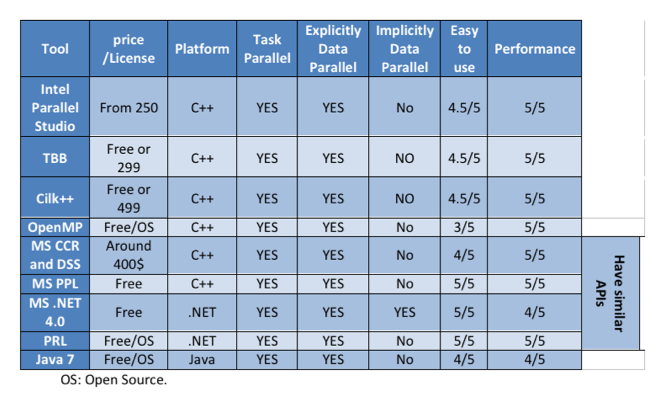

So what about the mainstream? Today, there is a big trend to make parallel computing more deterministic, and easy. There are many parallelism frameworks, and debugging tools aimed at simplifying the task of parallel programming, such as:

- Intel Parallel Studio

- Microsoft CCR and DSS

- MS PPL - Microsoft Parallel Pattern Library (will released in 2009 Q4)

- MS .NET 4 - Microsoft .NET Framework 4 (will released in 2009 Q4)

- Java 7 (will release in 2009)

- PRL - Parallel Runtime Library (Beta 1 released in June 2009)

In the following table I have compared the above frameworks:  The parallel framework you choose should depend on your platform, and your application. For example, the Parallel Runtime Library is designed to work with high-performance computing environments. The Microsoft .NET Framework 4.0 parallelism API however, is designed to support extensibility, and a wide range of different applications.

The parallel framework you choose should depend on your platform, and your application. For example, the Parallel Runtime Library is designed to work with high-performance computing environments. The Microsoft .NET Framework 4.0 parallelism API however, is designed to support extensibility, and a wide range of different applications.

What you could find in a Parallel Framework

There are a number of key tools you may find in your parallel framework of choice. These include:

- Parallel APIs

- Concurrency Enabled Data Structures - Data structures designed to be thread-safe, which means they will not fault if multiple threads try to access, or manipulate their values at the same time. Examples include: Queue, Stack, Blocking Collection, Hash Table, Linked List.

- Other useful stuff such as event objects that make it easier to manage shared data. Examples include: Countdown Event, Waiting objects, and Mutex.

Conclusion

The number of cores on processor chips could potentially double every two to three years – in fact, by 2020, we may very well have microprocessors that have 64, 96, or even 128 cores. The challenge that faces us today is how to leverage the power of all these extra cores, without requiring a tremendous amount of programming effort.

Today, it’s clear that parallelism is an important consideration for applications requiring high performance and scalability, but the reality is that implementing a parallel application poses many challenges. Debugging tools and frameworks for parallel programming are maturing though, and promise to make parallel programming much easier for us in the near future.